This is the first part of my essay dealing with the notion of the Self in the empiricist tradition. You can read the second part here.

Introductory words

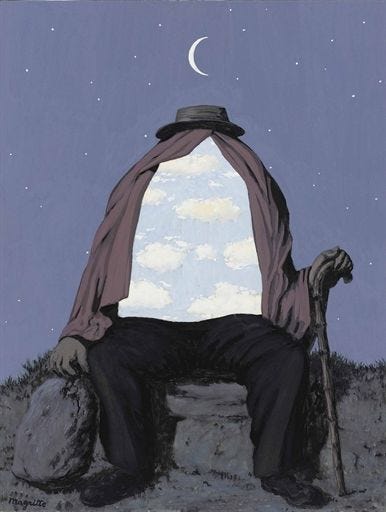

Isn't the Self like a lake that I’m endlessly trying to escape with the clear knowledge that I might not succeed? A lake whose boundaries I cannot grasp, whose shore I fail to reach, though I assume its existence beyond these unruly waters. It’s as if I’m forcibly cast into myself and into it. I – that is it. No one can confirm or deny with absolute certainty that the lake I’m in indeed is, no one but myself. An endlessly puzzling and frightening situation for us if this is indeed the case. In its isolation and solitude – a lonely water among countless miles of sands and boulders, a lone subject among objects – I find the millennia-old horror. It prompts me to problematise, to interrogate how it is possible, if it’s at all, this isolated existence of the Self in which I’m perpetually referring and contained to and within myself.

The history of philosophy, like any other history, undergoes several transformations in the conceptual layout of its basic, principal concepts. The self is one of those whose semantic plenitude is difficult to grasp. This is so because it’s precisely what the foundational inquiries are concerned with. "What am I?" is a constitutive and ground-shaping inquiry of our being. The others, of course, are its derivatives. First I will ask what I am, and only then where I come from and where I am going. They are derivative, but that does not make them insignificant, for they are confirmation of the complexity of the inquiry, of its magnitude, and also that only when we answer the first, will we be able to answer them. But how, how can we answer? And is what has just been said so at all? Is it the fundamental question, or are they, altogether, purely and simply derivative of the eternal striving of the questioning monster? Can we separate them, elevating one above all others? Here are a few more inquiries. History reminds us that each age asks its questions about the self differently, or rather, answers them differently. In the end, the truly important thing is the very fact of asking. As we ask, we puzzle; as we puzzle, we go, hopefully – forward.

Asking about the nature of the self, we are asking what this acting, active subject is that relates to the world around it, and interprets it in its unconditional and unceasing making-giving with things and objects. What is it that distinguishes it from others, if there are any, subjects whatsoever? Is it a distinction of degree or a substantial one? Or, more precisely, what makes the self something intelligible, the knowledge of which alone can enable it to continue to be, in a full-blooded way, if it's to follow the eternal covenant of the Delphic temple?

Turning to Antiquity, we do not find in it a notion that overlaps openly with selfhood as it comes to be seen in early modernity. While in the time of early, passionate Christianity (and in the work of St. Augustine in particular) we find the beginnings of such a psychologisation of the self, it is not until the High Middle Ages, including in pre-rationalist thinkers such as Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas, that we can speak of even approaching its outright autonomy. Their wandering in the limiting shackles of ancient thinkers prevented them from expanding the concept of self to the extent necessary to unify it under a single, clearly stated definition. As an example, we may point to the conception of persona or individual human being as a union of form and matter. Of course, this unity comes predetermined from something else, from the substance of all substances, i.e. God. The Self, in scholastic philosophy, is most often thought of as detached from the first intelligence, the first and only true substance. But, of course, that’s not enough. I’m making a broad generalisation here, that doesn't serve well all the tendencies and debates happening within the theological circles during this long-lasting dominion of Christianity. However, it helps us clarify the break.

Only with Descartes, this unitary substance would be swept away and the Self will start to be seen as a union between two independent substances – body and soul. Perhaps it’s precisely Christianity's inability to delineate the individual, to draw its boundaries, and to explicitly derive the Self and its already over-ripe ratio from dogmatic beliefs accumulated over the centuries, that lays the groundwork for its demise and, consequently, the rise of the autonomist interpretation of the Self. Of course, the consequences of such a development are what we are currently experiencing – an immense deification of selfhood. The problem with ideas is that we can never know how far their influence will extend. When will their usefulness be superseded by their menace?

The absolutisation, together with its idealiсation, led to the "Century of the Self," as a famous documentary series puts it. The 20th Century is devoted to the legacy of thinkers such as Nietzsche and Freud, who managed to shape the concept of selfhood in a way never thought of before. It was the New Age, however, that fiercely explicated its autonomy and set the stage for such a radical redefinition. Little by little, modern man became the dominant, the universe – his subordinate. Thus, it's placed upon the Self that definite emphasis will elevate it to the self-contained and even isolated existence saved for deities. We know this "I" well, for the "isolated I" is more or less every one of us.

Rationalists are the first to shape these new views. Perhaps they are the ones we should blame. The Self is once understood as some thinking substance or cogito (in Descartes), at other times as an independent monad (in Leibniz), at others as a modus of the original and indivisible substance (in Spinoza, which might look like a step back, but from our contemporary, post-Deleuzian perspective, it’s not), but in all three cases it seems to be left to itself despite the guarantors, and in all three – the Other is absent. And what is the self without the Other? Nothing. There is no I without a Thou. Therefore he could not be. Martin Buber's famous dialogical dyad is impossible here. The main problem is not the absence of axiological thinking, or rather, it’s not only in it.

In the misplaced epistemological framework, insofar as we should look for hope in the rediscovery of the otherness and dynamism of human existence, we find only isolation and self-sufficiency. Even if there are certain hints of otherness, this otherness is always transcendent, which is to say (as Kant would observe) – always unattainable, because somehow always manages to elude us by remaining outside the boundaries of the knowable. In the present essay, I will consider some of the views of John Locke and David Hume, opposing the foundationalist conceptions of the rationalists, and in part, each other, and my aim will not be to remain indebted to the implications of their claims. Indeed, quite the opposite.

John Locke

With John Locke and his “Essay Concerning Human Reason", we delve deeper and deeper into the idea of a subjectivist interpretation of identity already outlined by Johannes Klauberg, Thomas Hobbes and Robert Boyle.1 That’s why is important to first sketch in rough strokes one of the essential points where their philosophies intersect. The common thread is that identity – what holds selfhood the same over time, another question that didn't exist in previous times – should be seen in our relations to the objects surrounding us, be they concrete (this particular chair) or abstract (the chair in general). In this way, identity manifests itself as two-faceted. At one time it could be, roughly speaking, material, at other – formal. The example given by Hobbes concerns how identity is inquired about at all. If we ask about Socrates' identity in terms of 'this flesh and bones', in Aristotle's phrase, we are asking about his body and whether it’s the same at different times of observation. If we are asking about Socrates in terms of his form (or, to put it another way, personality, in Locke's terminology), we are asking whether he is the same person at different times. Our judgment therefore depends on our attitude, which is what we invest in asking about the constancy and homogeneity of the Self, and its identity.

Another point of extreme importance to note is that if some of the rationalists (Spinoza and Descartes, for example) start from definitions and axioms of general concepts (substance, infinite, etc.) or so-called innate ideas, the origin of which lies in their givenness to the cognising subject, coming from its rational community with God, what we have here is an attempt to explain and conceptualise their origins, rather than accepting them out of hand. In Locke, in particular, this situation is manifest in the advocacy of an understanding of human consciousness as a tabula rasa on which, thanks to experience, sensation and reflection, abstract ideas slowly but steadily build up.

But let us first consider Locke's relation to the individual things present in the objective world. Since he, like the other proponents of corpuscular philosophy, rejects the possibility of the existence of universals so deeply rooted in the debates of the centuries preceding him, the question of individuation is dismissed. Like Hobbes, Locke takes the basic nominalist position of the objective sameness of things, respectively of their unconditioned and absolute individuality, their objective identity. To say that a thing is precisely an individuality is to say that we find its, as it were, self-sufficient existence in a particular place and at a particular time. Thus the very problem of the principle of individuation (principium individuationis) is itself meaningless, for individuality is not a priori to existence as such, nor is it something that objects can or cannot possess, but is their very existence (or existence itself, "Experience.. "II, xxvii-3).

Such a position can be detected as a consequence of the corpuscularists' understanding of the particles constituting material things or material substances, which are to be thought of as individualities per se. Atoms or corpuscles (which is the same thing, except that it allows for an at least thinkable disentanglement) can be identical in their characteristics but differ in their spatiotemporal situatedness, which of course means that they are still different. But it's not just the individual atoms that are individuated by the very fact of their existence. The overall material composition of which they are part plays a role as well. Moreover, it (existence itself) individuates not only the substances (which are categorically divided into God, spirits, and bodies, like Descartes) but also their accidents. Hence the already profound, as it were, hyper-real being of objects, in which they aren’t merely a separate, independent concrescence, but constantly involved in the whole determination (as it is, for example, in Spinoza and Melbranche), drops out of the mental picture.

The truth of the general in Spinoza, which is eternal and immutable, and of which concrete existence is only a modification, permanently co-participating in this absolute, is displaced by the truth of this thing which is here and which I perceive in its immediate concrescence. The descent from the general and infinite, in the direction of the particular or individual, is here replaced by an ascent from the particular (to be more precise – from the perception of it) and its abstraction, in the direction of the general which is common only to the mind. This is perhaps why it’s more correct to say that Locke is a conceptualist rather than a nominalist. Everything said in this paragraph applies in part to David Hume's positions, which I will discuss in the next part of this essay.

But if the immediate perception of the existence of the particular, which is an objective and undoubted fact, is the principle asserting individuality, then to think the essence is to think that same fact. Later Hegel would go further, arguing that with Locke "the immediate reality [or the appearance and perception of things in their concrescence] is the real and true, and philosophy is no longer interested in the knowledge of what is true in and of itself, and turns only to describing how thought perceives [italics mine] the given.”

Thus the main emphasis is not on the individuation of things, but on the permanence or durability of their identity, which in turn is a consequence of their distinctiveness. The ideas which consciousness possesses, as far as they are simple, are clear and distinct. Complex ones, on the other hand, are the consequence of the accumulation of simple ones. With Hume, as we shall see later, their generalization is in turn the result of associative thinking or likeness, which is a particular kind of habit of mind. “Rejecting substantial forms and the possibility of knowing the essence of substances, Locke believed that the answer to the question of the extent to which something can change without losing its identity would be found in the 'nominal essence.' Which is to say, in the abstract ideas we have about those things whose identity is under consideration.”2 We are hardly performing some kind of intellectual-conceptual verification, something that would later appear in an altered form, however strangely, in Hegel. There is a problem here that Locke does not answer, and perhaps does not even see: if there are no innate ideas (as made clear above), and (abstract) ideas are the result of our making-giving with things in the field of experience, how is it that it's thanks to them that we can consider the identity of a concrete object, since these ideas are themselves the result of our perception of this very same object or others like it? This is a problem that will only be solved by Kant's schematism.

In terms of the identity of the Self, some of what is described above remains valid. Locke's essential contribution is the introduction of a middle term between the already established soul and body. This middle term is consciousness, which, though everything else is subject to change, remains invariably the repository of identity or the sameness of a person. As I have already said, the subjectivist understanding unfolds here precisely because it problematises inquiry itself. Locke argues that in order 'to understand what identity means, and to judge of it as we ought, we must see what idea is signified by the word for which it is used, for it is one thing to be the same substance, another to be the same body, and, thirdly, the same person', but this is on the assumption that 'body', 'person' and 'substance' are 'words used to signify three different ideas'. He then goes on to say, "Whatever is the idea which refers to a word, such must be the identity" (II.xxvii.74). The self here, or the persona, is the person. Its enduring identity is sustained by its consciousness, which in turn extends as far as knowledge of "some past action or thought." Thus, selfhood is constituted as a continuity of knowledge of myself as the same principal actor at different times and in different places. Precisely because in Descartes the self is aligned with the non-extensible and non-material substantial part of man (respectively the soul), the problem of his identity through time would not be posed. There it’s hardly guaranteed.

For each of the subdivisions that Locke points out, the answer withholding the identity is different, but that is not what we are interested in. What is important for us is why the being of the Self, or the identity of it with itself, is thought of as disembodied at all, and not as any kind of disembodiment, but as linguistically determined, as if this language comes from somewhere else along with its meanings and significations as if it were not a consequence of the Self's encounter with the Other and our attempts to give ourselves, to unfold ourselves before him or her as something (possibly) knowable. Not that the empiricist position on the conditioning of language by impressions leads in the right direction at all. On the contrary. But I nevertheless have good reason to think that such a conclusion is an overstatement of the multilayered processes necessary for the differentiation of linguistic structures. The question of identity here depends on words, on concepts, particularly on their denotative meaning, which fully determines the over-objectification of the subject inherent in dictionaries. It misses the profound dynamics of human being-in-the-world. This world is not only that of subject and object, which relate to each other in a constant and full-blooded intensification, but it's first and exclusively intersubjective, i.e. it's a common-with-Others world, otherwise language itself would be superfluous. This kind of abstraction from the co-existent particularities, the simultaneously immanent and transcendent super-realities of the human situation is, of course, a consequence of the spirit of the times – a spirit which, thanks to the scientific revolution, tends to objectify everything, including itself. But this does not mean that such reasoning is correct since it wrongly brings thinking into the bosom of so-called scientific research "sobriety" and "impartiality," as if it were possible for the subject to impartially objectify itself. But lest I digress further, I will note that, despite its many shortcomings, which are, of course, such from the perspective of the present, there is something of crucial importance in the conception of the identity of the self that Locke develops. Although he nowhere gives a clear definition of what consciousness1 is, Locke's formulation of it being bound up with one's actions and thoughts (II. xxvii. 9) as one's own, which holds it precisely as the same person (or persona) at different times, helps to make sense of us as moral beings in the first place. What the Self is, of course, is thought here not through its substantiality (material or not) but through its activity, i.e., experientially, whether directed outward or inward, and it’s here that the achievement lies.

1 Udo Thiel, The Early Modern Subject: Self-Consciousness and Personal Identity from Descartes to Hume; Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 102.

2 The Early Modern Subject, p. 103

According to some of his interpreters, Locke equates consciousness with either memory (see e.g. Thomas Reid) or reflection (see Kulstad 'Locke on Consciousness and Reflection', in Leibniz on Apperception, Consciousness and Reflection, 1991, and Leibniz himself in Nouveaux essais (II. i. 19) with his critique of the infinite regress to which the identification of consciousness with reflection leads, which 'always' accompanies every thought, which is itself again a thought on which it again reflects, etc.). According to others here, "It can do this [reason and reflect and consider itself...] only because of this consciousness, which is inseparable from thinking, and is, I think, essential to it" (II. xxvii. 9) it is evident that Locke emphatically distinguishes between them. But the truth is that a clear definition is absent.

we can't separate our doings from us, can we? How liberating it would be to think that no actions are our own.