The Notion of Truth

Bacon, Shakespeare, and the Author

"… writing is the destruction of every voice, of

every point of origin. Writing is that neutral, composite,

oblique space where our subject slips away, the negative

where all identity is lost, starting with the very identity

of the body writing."

Roland Barthes, The Death of the Author

There where times when Roland Barthes wasn't born yet. Times in which Shakespeare was very much alive and thriving (not that he isn't very much alive and thriving just yet). Back at those days, the author was probably important, even though there weren't copyrights. He wasn't, in other words, yet dead. In the midst of those days the author wasn't yet someone who dwells within his own absence.

Or was he?

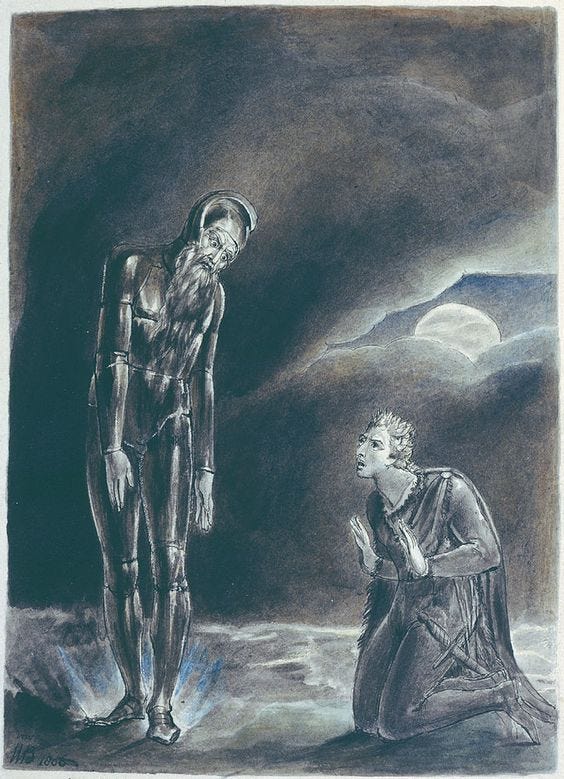

Guess only the bad ones. And the case of Shakespeare was, as it seems to me, precisely the sort of case for which it's reasonable to ask – was he alive in his writings or not? Is he still alive in his writings, if he ever was or will he ever be? I'll be talking here, therefore, about the specter of the author – someone who's very much alive and thriving, and yet somehow deceased, almost always already dead, within his stamped, imprinted flesh, within his both soundless and howling vitality, his body writing. Especially the good ones. It is the notion of truth that, one can argue, tries to find itself in this (post)postmodernist landscape of absolute relativity, to enforce the conditions of its own possibility.

But if there is single, really important statement that I'll try to emphasize here, it’s the truth of relativity, not the relativity of truth – a statement that very much aligns with what Barthes has to say in this relatively important essay of his. A statement that, I think, transcend the postmodernist landscape over to the discourse concerning the very nature of world literature, and even arts more generally.

So was it Francis Bacon Shakespeare, or it was Christopher Marlowe? Was it Edward de Vere, or it was Mary Sidney? We can go even further asking, was it Shakespeare Shakespeare himself? And here I'm not explicitly referring to the traditional argument concerning the “muses,” even though this might be at certain points of a given writing journey reasonably valid. My claim won't be that the author is a sort of a haunted puppet. Precisely the opposite is true, it’s the reader who is the puppet, haunted by the author, by the specter of someone, who isn't there and never was. At least not in the sense that my chair is beneath me. It’s this specter that talks, through the reader, to itself. It narrates to itself its own representation, the way it looks to everyone else. If this specter has pimples, badly brushed hair or eyebrows, only through us, as a readers, can it examine and understand itself. This is why criticism matters so much. At the same time, this is why great art stands somehow unreachable insofar as it achieves by itself and through us only its own absolute.

Here we find ourselves in yet another departure from basic understandings of great art, or literature, more specifically. Namely, that – thematically speaking – it’s seen as touching something that is greater than any of us individually, something affecting human beings as such, our very essence, they say. Great themes, this narrative argues, are ahistoric. And while the theme of, say, love is by implication ahistorical, it’s the way the specter of this past love looks towards itself through us and our present that makes it relevant. Thus the theme might be beyond history, cause we all love, and eat, and drink, and shit, and sometimes we are all mad, or jealous, creative or stupid, or have diarrhea, but all writing and reading has a historical topos. One can argue, that both writing and reading are a sort of topographical endeavors. A territorializing event of enormous proportions.

Moreover, as Barthes argues, the author as author, is a modern creation, a creation of Modernity. Shakespeare is a modern man, he is the last pre-modern and the first modern author, as well as the “prophet of postmodernity.” (Shakespeare and Modernity: Early Modern to Millennium, Hugh Grady; Routledge, 2000). The shift in those receptions comes to reaffirm the last claim of mine, that the truth about particular body writing is really an issue of territories, of contextual surroundings as governing determinants. Barth's example, serving to emphasize the language itself, its own speaking (a somewhat Heideggerian argument), the process of sublation of the author, Malarmé's work, strikes me as insufficient.

The conversation about who Shakespeare was, as a person, loses sight of the important conversation about when and, more specifically, where Shakespeare was. The territorialization in question begets intersection of both time and space. As well as their overcoming, of course. The truth about the decaying author's work is the truth about his when and where, his place. The only possibility of his specter haunting us is that his when and where is fixated at a significant intersection, conjunction or even dis-conjunction of different temporalities and spatialities, both geographical and sociological. Back to my major claim, it comes from/to a past, but also from/to a future territory that inevitably tries to make sense of the reader's present one. There is no other sense in which a body writing is ahistorical. Therefore, a dis-conjunction as this can only be thought, as Derrida put it, "only in a dis-located time of the present, at the joining of a radically dis-jointed time, without certain conjunction." (Spectres of Marx, Derrida, p.20) Of a time that, in Shakespeare words himself, is out of joint.

The possibility of wholeness, of unity in author's personality, of the truth about him, but also of writer's narrative's unity, dissolves within the lack of unity in his times. And precisely this lack lay the foundation for the question itself, the question that searches for a truth no one can or have to truly explicate.

Who was Shakespeare, then?

How can the son of a glover, who received common education for his years and class, a man for whom we have no records of attending an university, wrote what he wrote? Can Shakespeare, the man, ever be Shakespeare, the author?

For me the answer is no. Not because there is another personality behind Shakespeare. But because no author is ever identical to his personality, outside of authorship; because no personality is ever identical to the author, outside of personhood.

The truth of all creative work, the concept of truth lying in the work itself, is the reality of the reality depicted, not of the creator who depicts it.